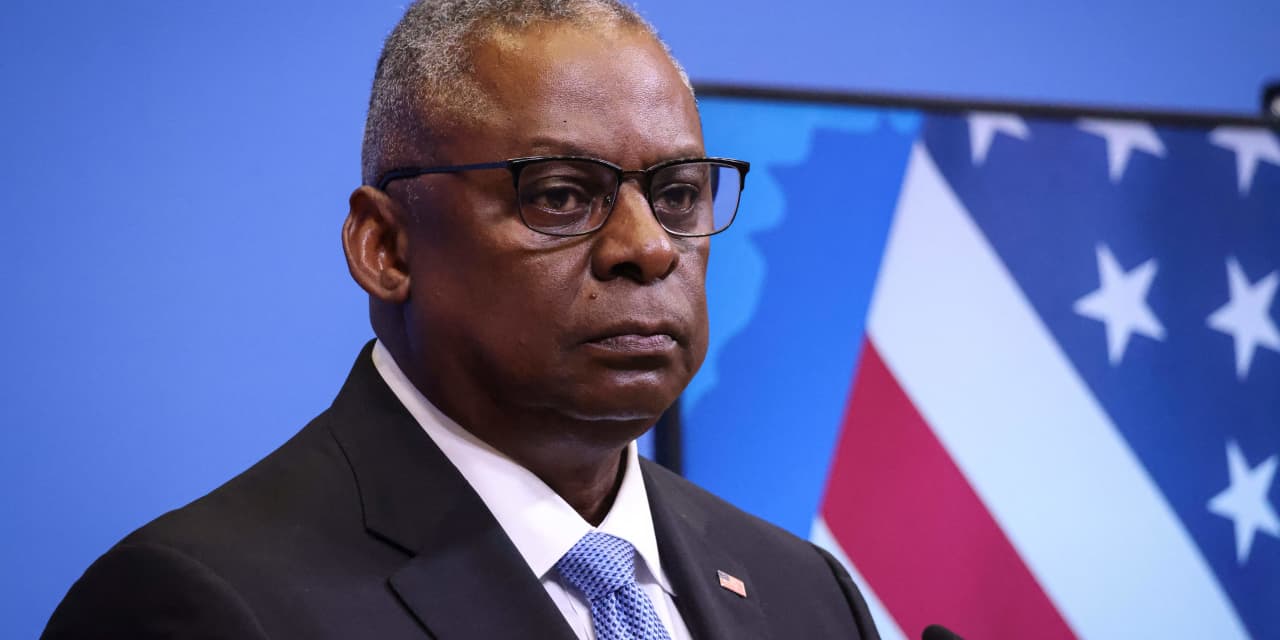

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin at the NATO headquarters in Brussels on Oct. 12.

Simon Wohlfahrt/AFP via Getty Images

Iran has been the shoe that hasn’t dropped ever since Hamas’s assault on Israel shocked the world on Oct. 7. Iran supports Hamas but hasn’t widened the conflict by joining directly or through its other proxies. That lack of a wider conflict has helped keep energy prices in check and other markets focused on factors like earnings, inflation, and interest rates.

But the risk of direct conflict with Iran remains high, and it isn’t clear that recent steps taken by the U.S. to deter it will work. The risks are most relevant to energy markets, a particularly sensitive part of the economy in an election year.

The trick will be in figuring when exactly the line has been crossed. The U.S. and Israel were already engaged in a shadow war with Iran before the Hamas attack. The violence has continued even as high-level diplomacy tries to limit its spread. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin said Thursday that U.S. forces in Iraq and Syria have suffered a series of attacks in the past several days. In response, Austin said U.S. forces “conducted self-defense strikes on two facilities in eastern Syria used by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and affiliated groups.”

That back and forth illustrates how the presence of U.S. forces can both lower and heighten conflict risks simultaneously. They can strike quickly if necessary, but simply being in a region where the U.S. has been a part of conflicts for decades is inherently risky.

Adding to that complexity are the ever-louder cries in the U.S. to limit Iran’s oil revenue. Yale professor Jeffrey Sonnenfeld led a high-profile campaign last year to drive U.S. companies out of Russia after its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Now he’s calling on the Biden administration to tighten the screws on Iran’s oil exports. “Iran must understand that if they continue to escalate, they will be in for a world of pain,” Sonnenfeld wrote in Time along with his colleague Steven Tian.

Iranian oil is a tempting target. Iran is already under heavy sanctions that likely force the country to accept discounts from importers like China. But its oil exports have been rising in recent years, and if sold at market value would be worth around $41 billion, estimates Jeffrey Schott, an economist at the Peterson Institute. That is more than enough to cover Iran’s costs for supporting Hamas, Hezbollah, and other malign actors, Schott says.

The Biden administration has been highly sensitive to how its actions abroad affect gas prices at home. It designed Russia sanctions to avoid crippling that country’s energy industry, and President Biden labeled the inflation from the war “Putin’s price hike.” Gas prices in the U.S. are down from the height of the war, at an average of $3.53 nationally, but AAA says they would be even lower if not for fears of a wider war in the Middle East.

That price point is going to become even more important politically as next November approaches. Frustration with the high cost of living is a big factor in President Biden’s low approval ratings.

The U.S. has drawn down its oil stockpiles on the Strategic Petroleum Reserve by about 50% in recent years. “As such the fire-power of its SPR as a geopolitical oil pricing tool is now somewhat muted,” writes Bjarne Schieldrop, chief commodities analyst at Swedish bank SEB, in a research note.

Saudi Arabia has plenty of spare capacity, and it has promised in the past to help with Iran-induced deficits in the oil market. U.S. refineries are also likely to see a surge in imports from Venezuela now that the U.S. temporarily eased sanctions in an effort to encourage democracy there.

That adds up to a lot of ifs hanging over the booming U.S. economy. Whether the sailing stays smooth depends on Iran and its other proxies getting the message and staying directly out of the fight Hamas has picked. It depends on authoritarian governments in Riyadh and Caracas opting to play ball with Washington. And those dynamics will play out against an election cycle that isn’t exactly favorable to rational discourse about evenhanded management of the economy.

Middle East hostilities have ramped up, which is likely to drive a prolonged period of uncertainty. Political actors could easily upset the balance in ways that shock markets. We’ll be watching for that shoe to drop for quite a bit longer.

Write to Matt Peterson at [email protected]

Read the full article here