What will define real success for COP28, with its focus on how global businesses and governments jointly manage the transition from fossil fuels to alternative energy sources over the coming decades? Part of the answer is that the conference will develop transition strategies that are consistent with the underlying economic cost-benefit valuations.

The President of COP28, Sultan Al Jaber, has expertise in both the fossil fuel industry and renewable energy industry. He is both the CEO of the United Arab Emirates’ state-owned oil company and a cofounder of the renewable energy firm Masdar. Moreover, Al Jaber is an economist. As a result, he is well placed to ensure that the key transition tradeoffs are analyzed using traditional economic valuation analysis, as encapsulated in the phrase “you pays your money and you takes your choice.” Will he do so? This question lies at the heart of whether COP28 will be a success.

“You Takes Your Choice”

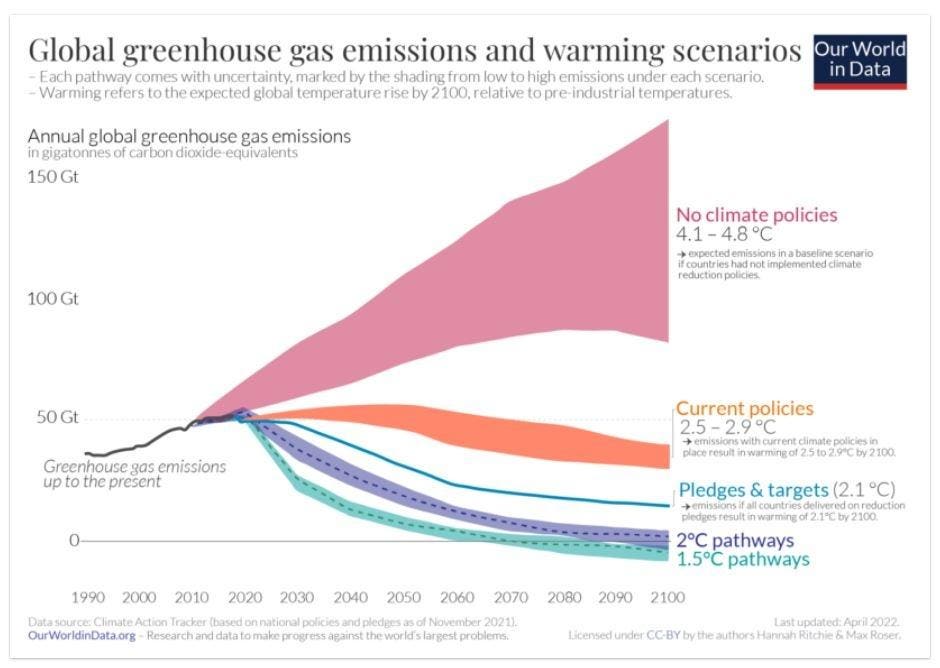

To understand the economic issues involving valuation and tradeoffs, consider the scenario choices in the following figure, which displays alternative greenhouse gas scenarios, as if all emissions were carbon dioxide.

The top pink set of scenarios illustrate plausible emission pathways if the world were to continue to follow business as usual behavior, as it has done throughout the industrial age. The orange group pertains to current policies. Below the current policies is a thin region of pledges & targets scenarios associated with the nationally determined contributions. Below the NDC scenarios are two aspirational groups, one pertaining to the achievement of 2°C and the other to 1.5°C. Notice that the bottom three scenario groups feature net zero emissions being achieved around mid-century.

To the right of each scenario group you will see the estimated associated end-of-century global temperature increases. For no climate policies, the temperature change rises above 4°C. For current policies, it is between 2.5°C and 3°C. For the pledge-based policy it is 2.1°C.

The above figure embodies consequences for temperature associated with the speed with which the global community transitions away from fossil fuels, if it transitions at all. In this respect, consider an analogy between climate policy choice and the choice of leasing an apartment.

One apartment option is to squat in an abandoned building, live unsafely, but pay no rent. That is akin to following a No Climate Policies scenario, for which I use upper case notation for ease of identification. A second option is to choose low rent substandard housing, which is somewhat uncomfortable but not as dangerous as squatting. This is akin to following a a Current Policies scenario. Choosing higher quality apartments entails higher rental payments, akin to a higher quality climate with lower global temperatures. Think of the bottom three scenarios in the figure as choices with successive higher quality.

“You Pays Your Money”

Next think about “you pays your money.” With the apartment leasing analogy in mind, consider the following question. Ballpark, what percentage of your standard of living would you be willing to sacrifice, maximally per year, to lease the planet from now until 2050 so that global temperatures fall between 2.5°C and 3°C instead of being above 4°C? For example, if your total consumption of goods and services per year were $100,000, how much of that would you be willing to sacrifice, maximally, to live on a 2.5°C-to-3°C planet instead of an above 4°C planet? In answering this question, keep in mind that currently, the planet has warmed by 1.1°C from the dawn of the industrial age. We know from experience how different the climate is now from just a few years ago.

The point of “pays your money” is to generate funds for abating greenhouse gas emissions. Abatement activities are varied but include transitioning from fossil fuels to alternative energy sources, capturing and sequestering carbon, trading carbon offsets, and removing carbon from the atmosphere. These are all on the COP28 agenda. Increased abatement is what produces a higher quality planet.

Please give a moment’s thought to answering this valuation question and the ones below. You will get more from continuing to read this post if you do.

Now ask the same question for the Pledges & Targets scenario. If your total consumption of goods and services per year were $100,000, how much of that would you be willing to sacrifice, maximally per year from now until 2050, to live on a 2.1°C planet instead of on an above 4°C planet? Repeat the question, but for the 2°C scenarios and then the 1.5°C scenarios.

There will be a spectrum of readers’ responses to the questions. Collectively, these responses identify the global community’s willingness to pay for different levels of emissions control. This is important because such valuations will be reflected in the market prices for carbon offsets.

These valuation questions are significant. As a community in dialogue we need to ask them explicitly. The issue is important because by avoiding these questions, we risk ending up leasing a lower quality planet than a higher quality one we would be willing to pay for.

In my new book, The Behavioral Economics and Politics of Global Warming, I discuss how economic models produce estimates about the kinds of sacrifice required per capita, to reach each set of scenarios. For No Climate Policies, it is of course $0 per $100,000 of consumption. For Current Policies, it is between $100 to $200, starting at $100 in 2025 and rising over time to $200. For scenarios relating to Pledges & Targets, and to 2°C, it is between $2,500 and $5,000 starting at $2,500 in 2025 and rising until the point when net zero emissions are achieved.

For 1.5°C, a lot depends on how quickly the global economy can move to net zero emissions, and whether it will be possible to achieve net negative emissions before 2045. The state of technological progress around alternative energy and greenhouse gas removal will be central issues here. A rough valuation estimate range for achieving 1.5°C is $18,000 to $77,000, starting at $18,000 in 2025 and rising to the top end of the range by mid-century.

The analysis used to produce the above economic estimates features an implicit assumption, namely that the global economy is efficient at reducing emissions.

Confronting Reality

Look again at where the scenarios in Current Policies lie relative to those in Pledges & Targets, let alone the scenarios for 2°C and and 1.5°C. The critical question for COP28 is the degree to which it will move it will induce a transition from Current Policies to the scenarios for 2°C and and 1.5°C.

Notice that the latter two scenarios entail declining annual emissions, beginning now. For Pledges & Targets, annual emissions peak about now. If COP28 leads to a further increase in the annual emissions rate, then we can conclude that the global economy remains in the Current Policies group. Would that qualify as a success?

In the end, the scenario which the global community follows will depend in large part on how much the community is willing to pay. A lower quality planet with higher temperatures is certainly cheaper than a higher quality planet; but, so is squatting. What makes COP28 an especially controversial COP is that out of self-interest, its leadership might steer the global community to a lower quality planet when the community is willing to pay for a higher quality planet.

Optimism is fine. However, the negotiations at COP28 need to incorporate honest valuation assessments associated with transition tradeoffs. The risk of not doing so is paying your money but making the wrong choice. You get what you pay for. If you only pay for substandard, you will get substandard. COP28 is a time to confront reality.

Read the full article here