President Biden’s industrial and trade policies are terribly controversial.

Economists, pundits and the media—on the left and right—complain these will promote inefficiency and won’t address fundamental disadvantages—for example, shortages of engineers and similar workers with advanced training.

Allies in Europe criticize that the Buy America provisions will weaken their industries.

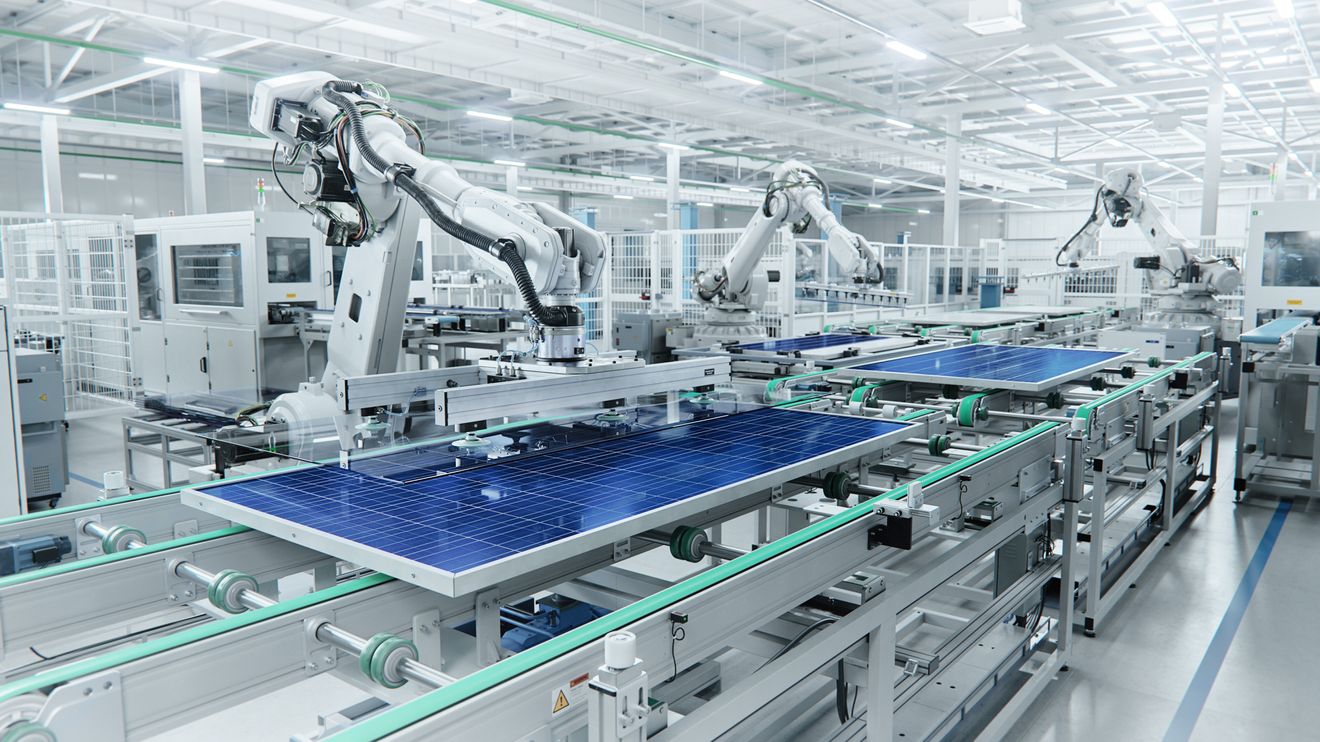

Much depends on how the CHIPS and Science Act and Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, are implemented. These offer subsidies and loans to promote scientific research, domestic production of alternatives to fossil fuels such as hydrogen and solar and the decarbonization of the economy through electric vehicles, heat pumps and the like.

Recognizing the vulnerabilities posed by excessive dependence on China, these incentives are intended to promote secure supply chains for advanced computer chips and batteries—from critical raw materials to packaged semiconductors for industry applications, storage for electric utilities and building EVs.

These incentives are critical to the U.S. achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2050. However, those are at loggerheads with U.S. commitments under the World Trade Organization, but not necessarily with U.S. bilateral and regional free trade agreements.

For example, the IRA offers tax credits of as much as $7,500 for the purchase of an EV if it is assembled in the United States, Mexico or Canada and its batteries contain at least 50% North American content—that rises to 80% by 2027.

As with computer chips, this will be more costly than sourcing more automotive parts from China, but the Biden administration counters that Chinese competitors enjoy lower costs thanks to myriad subsidies and protection. Progressives reasonably argue that much of the Middle Kingdom’s cost advantages for essential materials such as nickel, lithium and cobalt result from lax worker and environmental protections.

Those considerations along with the security risks of relying on China are too often ignored or discounted in the critiques of Biden’s industrial policies by mainstream economists.

The general exclusion of the EU and Asian allies from the tax credits and other financial benefits are inspiring them to create similar programs.

The fundamental problem is that Chinese trade and industrial policies are hardly consistent with the letter or at least the intent of WTO agreements, and the latter’s dispute settlement mechanism has proven impotent.

Consequently, the best alternative is to encourage Europe, Japan, South Korea and others to ramp up their programs and for the United States to cooperate with them.

This column has argued that a free trade system built outside the WTO—for example, anchored in the Trans-Pacific Partnership—would be highly desirable for achieving the specialization and economies of scale benefits of free trade while addressing the predatory economic consequences of China’s mercantilist policies and the security challenges posed by its military buildup in the Pacific.

The United States has negotiated a national treatment agreement with Japan for the production, processing and recycling of materials for making batteries. U.S. negotiators are moving toward a similar agreement with the EU. and this approach should be expanded to other allies.

This is hardly U.S. accession to TPP, but trade policy must recognize political constraints. And too often economics is inadequate to evaluate the social costs and security risks associated with unbridled international commerce.

Biden’s commitment to weighing the impacts of trade policy on domestic workers is laudable but too extreme. For example, he has rebuffed U.K. overtures to negotiate a free-trade agreement and a technology cooperation agreement. It’s hard to comprehend how U.K. working conditions and expanded cooperation and commerce with our strongest strategic partner would pose risks to American workers—other than fair competition.

That’s the rub.

Organized labor came out against the recent agreement with Japan. It wants the United States to extend national treatment only for five minerals that cannot be produced here.

Such an approach, generalized across most industries, would dramatically lower U.S. standards of living.

Quite apart from the policies pursued by the Trump and Biden Administrations, aggressive Chinese government actions in recent years to bring the private sector under tighter control and supply chain disruptions caused by COVID are inspiring American businesses to diversify sourcing.

A comprehensive analysis by DHL indicates that globalization is not going away—rather linkages are changing.

China continues to be a pre-eminent trade and investment partner, but American multinationals strengthening relationships elsewhere to mitigate risks—again supporting the idea that joining the TPP could promote U.S. prosperity and security interests.

If Biden is re-elected or a GOP candidate reflecting the preferences of Trump supporters captures the White House in 2024, U.S. accession to the TPP is unlikely.

A network of national treatment agreements to build out secure supply chains in alternative energy, chips, EVs and other industries that foster competitive specialization along the lines of the U.S.-Japan Critical Materials Agreement would be a good second-best approach.

Peter Morici is an economist and emeritus business professor at the University of Maryland, and a national columnist.

Read the full article here