The employment report for March gives plenty of good news for the U.S. macroeconomic situation. The economy added 236,000 nonfarm jobs, matching what had generally been expected. In fact, March’s 0.15% growth rate (1.8% annualized) was exactly identical to the average over the past 77 1/2 years since the end of World War II.

That’s perfect. Major softening in the job market would be an important sign that a recession is on the way, while too much strength in the job market would force more aggressive interest rate hikes. The March jobs report, though, suggests that we’re on exactly the right track.

If the economy is, indeed, heading for a “soft landing,” this is what it looks like.

As I noted a week ago, the Federal Open Market Committee will look for several key indicators of success in their fight against inflation. “A narrowing of the gap between labor supply and demand” is at the top of the list given by Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic, who as one of the Fed’s “doves” represents an important early-warning signal for any change in the FOMC’s direction.

The biggest surprise in the April employment situation was a downtick in the national unemployment rate from 3.6% to 3.5%. The FOMC members have been expecting it to rise above 4% before settling back to that as a long-term target, so the downtick might seem like a “worsening” rather than a “narrowing” of the gap between labor supply and demand. That is not what is happening, though.

Employment-to-Population Ratios Suggest Workers are Coming Out of the Shadows

The problem with the unemployment rate is that it counts only for people who “actively looked for work” during the previous four weeks—meaning that it does not count other workers even if they want a job and could take one. As Lael Brainard—then a member of the Federal Reserve Board, now Director of the National Economic Council—said in a 2021 speech, “Although the unemployment rate is a very informative aggregate indicator, it provides only one narrow measure of where the labor market is relative to maximum employment.”

Because of this, FOMC members typically take into account broader measures, such as the Employment-to-Population Ratio (EPR), to judge whether there is the right amount of “slack” in the job market, meaning that employers can find available workers without having to bid up wages dramatically.

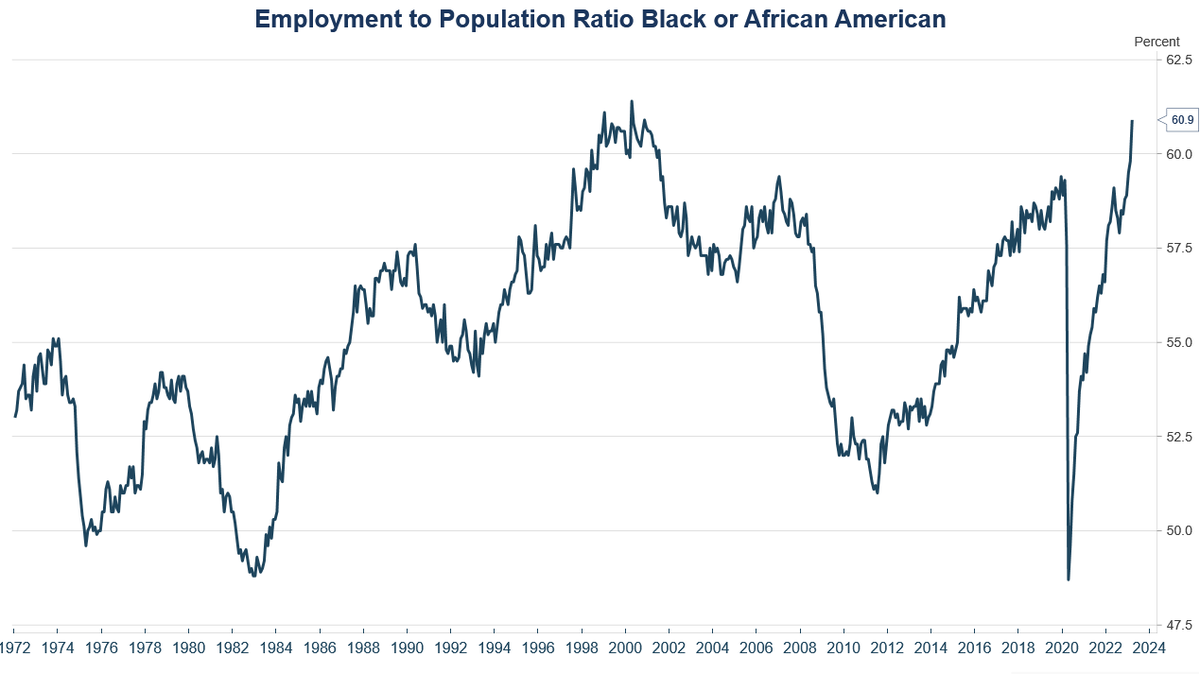

The EPR for specific vulnerable groups is especially informative of labor market conditions, since those groups are often the last to be hired when the job market is strengthening and the first to be let go when the job market is weakening. That is why the EPRs for those groups—youth, women, Hispanic, and Black populations—provided the best news in a good-news March job report.

The brightest star was the EPR for Black or African American adults (age 16+). At the beginning of the covid pandemic it plummeted to just

just

A record-high EPR or a record-low unemployment rate would be a sign of an overheated job market—requiring more aggressive hikes in interest rates—if we were talking about prime-age white men. The unemployment rate for white men, however, held steady for the third straight month at 3.2%—indicating that there is still room for improvement in the employment conditions of Black workers. And the EPR for white men has recovered only to 68.0%, smack in the middle of the range that was normal for them from the conclusion of the 2008-09 financial crisis to the onset of the covid pandemic.

Other vulnerable groups of workers are showing similar success in the job market: strong EPRs, but not evidence of overheating. For white women the EPR in March was 54.5%, higher than the level prevailing during 2010-17 but lower than was common from 1993 until the financial crisis. For Hispanic workers the EPR has ranged recently around its March level of 63.7%—again, higher than was typical during 2010-17 but lower than the levels common from 1999 until the financial crisis.

As Federal Reserve Board member Lisa Cook said on March 31, “wage moderation may partly reflect some improvement in labor supply. Labor force participation edged up to 62.5 percent in the most recent data. Prime-age participation is now back to pre-pandemic levels.” In short, it does seem as though the economy is finding its more vulnerable workers, but not straining to do so.

What Does This Mean for Interest Rates?

One thing that FOMC members have made very, very clear is that they want to make sure to kill inflation, not just injure it. Federal Reserve Board Chair Jerome Powell has repeated, over and over again, variations of the wording he used in a press conference in June 2022: “There’s always a risk of going too far, or not going far enough…. But I will say, the worst mistake we could make would be to fail, which—it’s not an option. We have to restore price stability. We really do.”

That almost certainly remains the prevailing view among FOMC members. Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester repeated a version of it on April 4th: “In my model projection, to put inflation on a sustained downward trajectory to 2 percent and to keep inflation expectations anchored, monetary policy moves somewhat further into restrictive territory this year, with the fed funds rate moving above 5 percent and the real fed funds rate staying in positive territory for some time.”

Mester is known as a “hawk,” among the group of FOMC participants who tend to place more emphasis on fighting inflation than on fighting unemployment and who therefore tend to favor increasing interest rates rather than reducing them. What is most important, however, is that the “doves” are making the same call. One of them, Federal Reserve Board member Lisa Cook, said on March 31 that “what should not be uncertain is our commitment to our dual-mandate goals of maximum employment and price stability. We will do what it takes to bring inflation back to our 2 percent target over time.”

The Fed’s famous “dot plot,” reflecting the views of FOMC participants as of the March 22 FOMC meeting, shows that only one thought that the key Federal Funds rate should remain below 5% during 2023; the largest group thought that the 5%-5.25% range would be appropriate, but seven members thought that rate hikes would have to continue beyond that.

The March employment report probably does very little to change those dynamics. It was not noticeably strong, it was not noticeably weak; it was just right. Given that the FOMC participants have expressed such unanimous support for its current rate-hike regime, it would have taken a noticeably weak employment situation to head off an increase at the next meeting.

In other words, even if the next rate hike may turn out to be the last, the recent careful pace of interest-rate increases, like the pace of employment growth, seems not too strong and not too weak: it seems just right.

Read the full article here