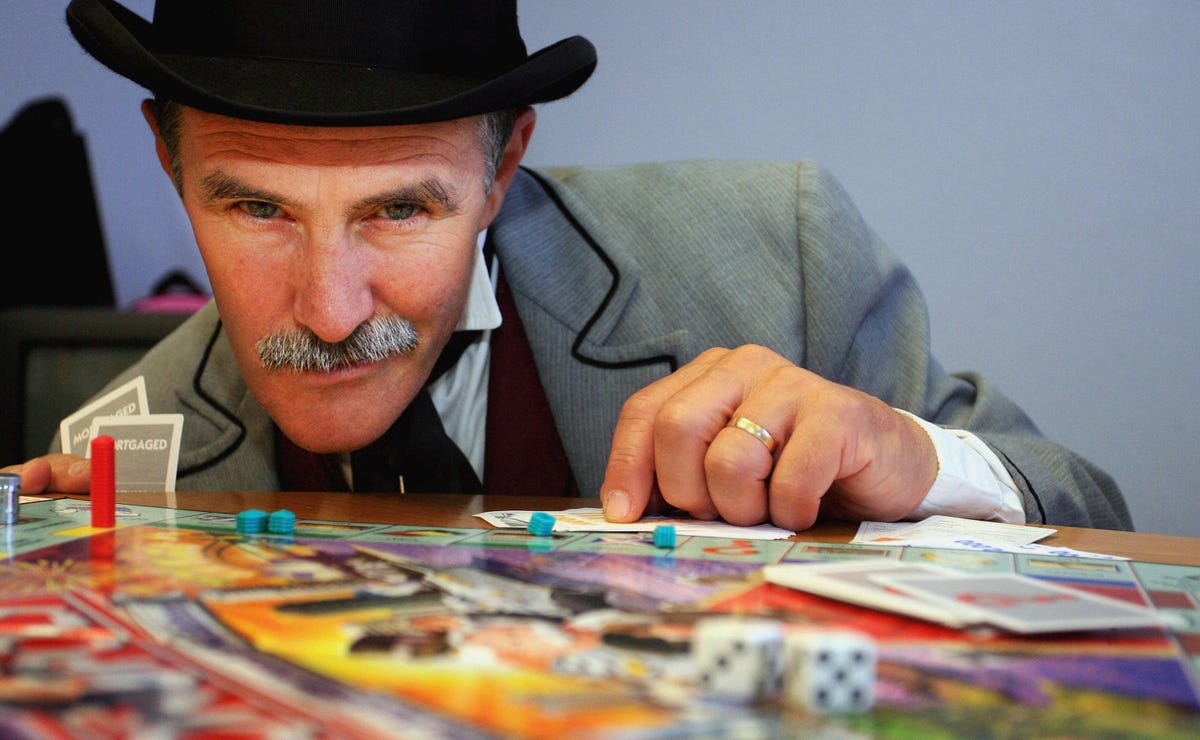

In early 2019, back when the idea of a global pandemic was limited to sci fi movies and video games, I wrote a column exploring how cannabis companies were being valued and the land grab that was happening at the time. Back then, cannabis capital markets were at all-time highs, despite most companies having relatively low revenue or profits, largely based on speculation over which companies were best positioned to dominate the then-nascent cannabis industry. As US multistate operators (MSOs – as large US cannabis companies have now come to be known) spread out to seemingly take as much territory as possible, I likened the game they were playing to two classic board games most of us know from our adolescence: Monopoly and Risk.

The start of a game of Monopoly is often a land grab. There are limited chances to buy territory, so whatever you land on you generally pounce on the opportunity to buy. Even if it does not fit your other territories later, you have a reasonable chance of being able to attain at least some value for it through trade or through blocking other players from achieving a monopoly. There is very little downside in land grabs in Monopoly. And, Monopoly by design limits how deep you can go – three properties with hotels and you’re done.

Risk, on the other hand, is a game of all-out conquest to control the entire world map. A critical thing in any game of Risk is not necessarily how much you control at the start, but where you position your limited forces to be most effective in your campaign to assemble more territory. Where Monopoly the incentive is to go wide before you go deep, in Risk it is exactly the opposite – you want to go deep before you go wide and failing to do so usually means a fast end to board game night. Risk’s limits on how deep you can go in any territory are much higher than Monopoly, but the limited army you have prevents you from going deep and wide at the same time.

I likened the 2019 state of affairs to MSOs playing a game of Monopoly. Many of the largest companies in the space were engaged in a land grab to get as big as possible as fast as possible, usually with a focus on limited license markets where regulations limited how many competitors they could have but, generally, not how deepthose competitors could go in that particular market. MSOs also treated grabbing land as having no downside like in Monopoly – the more territory grabbed, the merrier, not realizing in those halcyon capital markets days of focusing on “Total Addressable Market” that the wind could shift and that a poor territory could actively drain the company’s resources. Instead of playing Risk, and going deep into the markets where they stood the highest chance of sustainable revenues and profits, they tried to go deep and wide. I suggested back then that the smarter way to play the US cannabis game was like Risk, not Monopoly, and that eventually capital markets would shift their valuation metrics from speculation and total addressable market to more traditional business metrics like revenue, EBITDA and earnings multiples – and it seems those days are at least starting to come.

Looking back four years later, it is clear that the market has shifted, and cannabis companies are now being judged as much or more on their operational competency and ability to generate cash flow

flow

Let’s start by exploring the major mergers and acquisitions at the time the original article was published in May 2019. At the time I wrote the following:

In the past year, we’ve seen announced or completed mergers between iAnthus and MPX, MedMen and Pharmacann, and Harvest and Verano. My own company 4Front has announced a merger with the Washington State company Cannex.

Outside of the 4Front – Cannex merger, these all could have been categorized as mergers of assets rather than skill sets. In other words, they were Monopoly moves. Once the cannabis stock market collapsed, or right-sized depending on how you look at it, many of these deals were no longer commercially viable. Two of them, MedMen – Pharmacann and Harvest – Verano fell through before they were completed (Harvest went on years later to merge with Trulieve). While the iAnthus – MPX deal did go through, the company effectively went bankrupt shortly thereafter (cannabis companies cannot file for federal bankruptcy protections because the production and distribution of cannabis remains illegal under federal law).

And iAnthus was hardly alone. Back in 2019, if you asked anyone outside of the industry to name a cannabis company, the only one they could likely name was MedMen. At the time they were the darlings of the cannabis capital markets, appearing regularly on CNBC and cable news. But while the company focused heavily on acquiring high profile assets and boosting their brand through marketing, they weren’t profitable. When the capital markets eventually dried up, the company did not have the operating budget to sustain itself and was effectively taken over by its creditors who attempted to sell it for parts, a saga continuing to this day.

Meanwhile other large companies were forced to put increased emphasis on operational competency and efficiency in order to survive in the evolving cannabis landscape. Many companies who staked their futures to limited license states saw those states’ regulatory environments change as they shifted from medical to adult use. Highly valued states like New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts all converted to adult use and eliminated their license caps altogether. Today, only a small few adult use states have license caps, and most of those are large enough that they effectively operate as unlimited license markets.

Unfortunately, my prediction that capital markets would ultimately shift to evaluating businesses based on traditional business fundamentals and reward those who run efficient high-quality operations has not exactly come true, at least when it comes to public companies. Instead, valuations seem to be driven by a different kind of speculation, this time over anticipated regulatory and legal changes. When the Democrats took over both houses of Congress in January 2021, cannabis stock prices spiked to all-time highs, not because the business fundamentals of the public companies had changed, but because markets saw the political shift as a sign that Congress would enact SAFE Banking, providing access to institutional capital and traditional lending.

Over the next two years, as time dragged on with no banking reform, stock prices methodically trickled down, with momentary spikes largely driven by the latest rumors about potential movement on SAFE. When SAFE eventually failed to pass at the end of 2022, cannabis stocks plunged to new all-time lows, where they have largely remained in the opening months of 2023.

If you look at the stock charts for the past four years of nearly all public companies in the space, they follow virtually the same pattern. It is inconceivable that every company in the space has had nearly identical financial performances, yet the stock prices have largely moved in unison.

While the capital markets may not fully differentiate between effective operators and license aggregators just

just

It is possible that the current climate will be the new normal for the foreseeable future. While Congressional leaders continue to look for a solution to the cannabis banking issue, there is a real likelihood that nothing gets passed through a Democratic controlled Senate and Republican controlled House. Very few laws are expected to pass in this political environment and there’s little reason to believe cannabis will be the exception.

While the capital markets may not yet value operational efficiency, businesses are being forced to make cuts and streamline operations in order to run cash flow positive businesses. A prolonged cannabis capital downturn may wind up being the catalyst for companies, and eventually markets, to view sound business practices and traditional operational metrics as paramount to running a successful cannabis company. With no investors to bail them out, companies are now forced to focus on healthy balance sheets or face a genuine extinction event for their businesses. But the question I still have four years later is: have they learned to stop playing Monopoly and start playing Risk?

Read the full article here