As investors peer into the coming year, one thing is eminently clear: Namely, what is top of the mind for them is whether the Federal Reserve is finished raising interest rates and will lower rates next year. While interest rate expectations always matter, the gyrations of financial markets – stocks, bonds, and the dollar — the past two years have been dominated by expectations about what the Federal Reserve will do.

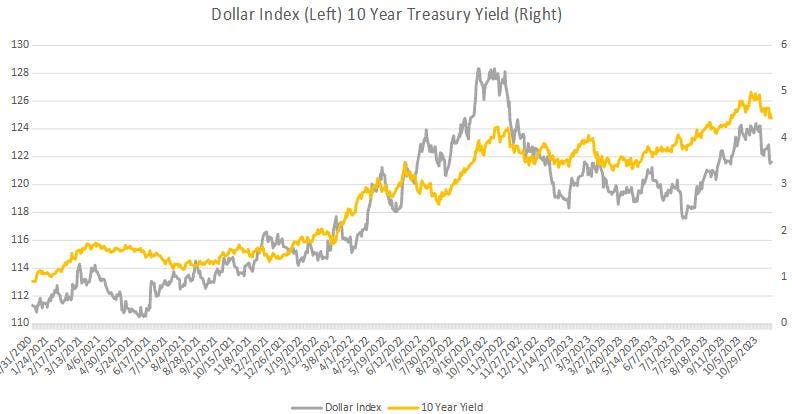

The first chart shows there has been a close correlation between 10-year Treasury yields and the trade-weighted dollar index over this period. Bonds have sold off (yields have increased) and the dollar has rallied when investors believed the Fed would raise rates. Conversely, yields have fallen and the dollar has weakened when investors anticipated an end to Fed tightening.

The second chart shows that the stock market and bond market also moved in tandem for most of this period. (Note: The right-hand axis for bond yields is inverted to facilitate the comparison). Prior to June of this year, both markets sold off when the Fed was expected to raise interest rates and they rallied when investors believed the Fed was done tightening.

The two markets diverged in the third quarter, however, when real GDP growth turned out much stronger-than-expected. This caused bond investors to throw in the towel that the Fed would lower rates and 10-year Treasury yields spiked to a 15-year high of 5%. The stock market advanced, nonetheless, as equity investors took comfort that the risk of recession had lessened.

More recently, both the bond market and stock market have rallied significantly amid favorable inflation readings and signs that the labor market is moderating. The bond market is now pricing in that the Fed will lower the funds rate by 75-100 basis points next year beginning in the spring, and stock investors appear to concur with this assessment.

The main problem with jumping aboard the bandwagon, however, is that investors have been wrong in anticipating Fed policy over the past two years.

According to a research report by Deutsche Bank cited in Markets Insider (November 17), the U.S. stock market has incorrectly priced in a Fed pivot six times over that period. Deutsche Banks’ economists caution that while Fed rate cuts are possible next year, the final stretch in bringing inflation down to the Fed’s 2% target rate tends to be the most difficult. Indeed, Fed officials have indicated they are not ready to declare the inflation fight is over, and they caution that there could be a further tightening if the economic data warrant it.

So, weighing these considerations, how should investors be positioned?

My take is there are two main considerations that will influence the Fed’s decision on rates.

The first consideration is Fed officials want to be sure that core inflation, which excludes the volatile food and energy components, is well on its way to approaching its 2% average annual target. This is a necessary condition for the Fed to leave rates on hold.

It does not mean that the core rate must reach 2% precisely, but Fed officials would probably need to see the rate fall below 3% to be convinced they are within striking distance of their goal. The Fed’s latest projections as of September suggest this outcome is possible, with the median forecast for core PCE inflation at 2.6% in 2024 and 2.3% in 2025. Although Fed policymakers are reluctant to declare the fight to lower inflation is over, they could shift to a neutral stance before long.

The second consideration is that in order for the Fed to ease monetary policy it must be convinced that the economy is weakening. The key indicator it will use to render this assessment is whether there is evidence of slack in the labor market.

What is striking about the Fed’s assessment, in this regard, is the latest projections do not indicate Fed officials are particularly worried about rising unemployment or a recession. Indeed, the unemployment rate is projected to hold steady at around 4.0%-4.1% through 2026, while the economy is expected to grow close to its potential rate of 1.8%.

This is where the Fed’s forecast is most likely to be wrong. While the economy has proved to be remarkably resilient to Fed tightening thus far, there are some signs of cracks in the economy. The most glaring is the housing market, where the combination of rising home prices and 30-year mortgage rates in the vicinity of 7.5% have left homes unaffordable for many prospective buyers. The manufacturing sector is also weak owing to higher interest rates and a strong dollar. And consumer fundamentals are showing some deterioration as household saving for low- and middle-income groups are being eroded.

In these circumstances, labor market conditions are likely to continue to moderate and the unemployment rate will probably drift higher in the coming year. If unemployment were to reach 4.5% or higher, I suspect the groundwork would be laid for the Fed to ease rates, as it would indicate there is slack in the economy that would lessen the risk of a resurgence in inflation.

The extent of Fed easing would ultimately hinge on whether there is a recession. This remains a close call as there is typically a lag of a year or more between the end of Fed tightening and the onset of recession.

All told, my conclusion is that bond investors may finally be right in anticipating rate cuts next year with more to come in 2025. However, the extent of Fed easing will depend on how worried it is about a possible recession and financial market instability.

Read the full article here