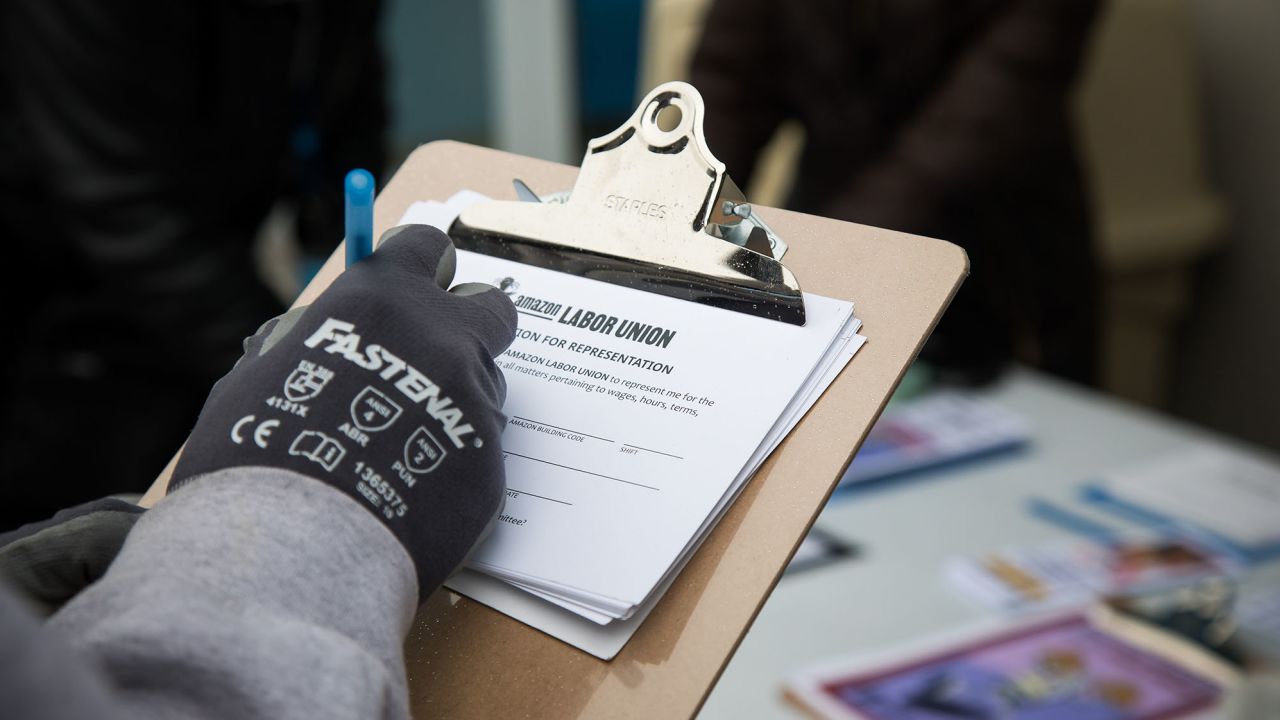

When the Amazon Labor Union shocked the world last April by successfully forming the first US union in the e-commerce giant’s history, Chris Smalls, the president and face of the organization, celebrated by making champagne rain on the street and thanking Jeff Bezos “for going to space” while workers organized.

Smalls, a worker who was fired by Amazon

(AMZN) in the early days of the pandemic and then labeled as “not smart or articulate” by a company lawyer, quickly emerged as an icon for the resurgent US labor movement. He went on a media tour that took him from the red carpet to the White House, often clad in his “Eat the Rich” jacket and Versace sunglasses.

But in the year since the landmark victory, Smalls and ALU appear to have fallen back to earth. Amazon still refuses to recognize the union or come to the bargaining table, dashing the Staten Island workers’ hopes of creating their first contract. The group fell short in its campaigns to organize two other Amazon warehouses in New York, including one across the street from the unionized facility. Meanwhile, Smalls and the union have been grappling with public infighting which, combined with its stalled progress on other fronts, could threaten the union’s future.

The early struggles for ALU highlight the challenges of taking on one of the biggest employers in the world. It has also renewed questions about whether a grassroots organization, rather than a more established union, is best suited for the task, even though no established union has ever made it this far in organizing a US union at Amazon.

“I think that’s a lesson here, that an established union would have helped the local leaders in these internal battles to get worked out, and to help them prepare and structure a bargaining approach and strategy,” said Thomas Kochan, a longtime labor researcher at the MIT Sloan School of Management’s Institute for Work and Employment Research.

But in a recent interview with CNN, Smalls was enthusiastic about the state of his union, noting that “it’s been going great,” while pointing to the realities of being a grassroots group.

“If anybody could do it better, please be my guest,” Smalls said of running ALU. “This is not an established union that’s been around, this a grassroots movement that’s going to have growing pains, and there’s a lot of uncharted water because it’s never been done before.”

“Our expectations is insane,” he added. “People expect us to be moving like we’re an established union that’s been around for 100 years. That’s not the case, we’re as grassroots as they come.”

When Heather Goodall and her colleagues started organizing at an Amazon warehouse in Albany, they met with representatives from multiple established unions, including the Teamsters, to discuss the effort. But ultimately, they decided to organize with ALU.

In the grassroots group, Goodall initially saw a fighter. The union, founded by Smalls after he was fired from the Staten Island warehouse following his decision to lead a protest over pandemic working conditions, was the one group to actually “beat the billion-dollar bully,” as she put it to CNN last year. And the decision of the Albany workers to organize with ALU suggested Smalls’ group could extend its influence throughout Amazon’s sprawling network of warehouses.

Instead, ALU lost the fight to unionize in Albany in October and tensions later boiled over between Goodall and Smalls, with the Albany organizer telling CNN she pushed back on Smalls’ pay, travel and leadership.

“I told Christian, ‘We have a problem, you need to stop traveling, you need to focus on the workers,’” Goodall told CNN. “I wanted to protect the integrity of the ALU, so I kept it internal, but some of the challenges that I was arguing with him about started to really shake the foundation of the ALU.”

Goodall said the tensions only increased in January, when she said she learned Smalls was earning a salary of $60,000 from the union, and as she questioned how much was being spent by the group to rent office space in New York City.

“I started to realize that Christian had really convinced himself that he is the end-all and that’s not how a union is run,” Goodall said. “That was kind of the beginning of end.”

Goodall said she was told to “get on board” and when she continued to raise concerns about union leadership, she said she was eventually removed from her role as chairperson for the ALB1 Amazon facility, and stopped receiving her $300 weekly paycheck from the union in early February.

Smalls, for his part, did not directly address the claims about her removal when asked. “First of all, there is no infighting because they’re not in,” he said.

Smalls said that “every union president in this country travels” and defended his salary as a fraction of what other union presidents earn. He said he sees his travel as important for getting young people excited and involved in the broader labor movement, saying, “I’m fighting for workers on a greater scale.”

He also said he earns money from some of his public appearances, but added that, “I put my life on the line long enough,” after spending more than 300 days unemployed and at the bus stop across the street from the Staten Island facility trying to unionize it. “My speaking engagements is yeah, for my own personal well-being, I was out of a job from 2020 with no help, I have a lot of bills and a lot of debts that I accumulated that I need to get rid of.”

And despite now rubbing shoulders with celebrities like Zendaya, appearing on Time’s list of the 100 most influential people and gracing the cover of New York magazine, Smalls insists the fame hasn’t changed him. “I’m still a worker who was fired three years ago during the pandemic,” he said. “I’m the same person who I was in 2020, I’ve always done as much as I can, I’m only one person and I can’t be at every place at every given time.”

Even with her criticisms, Goodall echoed Smalls in calling the infighting at the organization “growing pains” for the budding union and said she is hopeful that ALU will soon make a “comeback.”

“I don’t care about the money, I’m continuing everything that we’ve been doing,” Goodall said.

“This can be a learning experience,” she added. “We are going to elect strong leadership and we are going to make this a historic movement going forward and make it about the workers.”

The union’s stated goal is to fight for better pay, benefits and working conditions for warehouse staff. For ALU to prove itself now, it ultimately needs to be able to get Amazon to the bargaining table and secure its first contract for workers at the Staten Island facility — and show workers that it can win some negotiations with the e-commerce giant.

“They’re under a lot of pressure,” said Kate Bronfenbrenner, the director of labor education research at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations, “because they went around talking about what a great victory they have. Then everybody says, ‘Okay, what’s next?’”

Bronfenbrenner, who is also the co-director of the Worker Empowerment Research Project, an interdisciplinary network of labor market researchers, added that not having a first contract a year after an election is “not a big deal” for the union, as “only a third of a third of newly-organized workplaces” meet this milestone in that timeframe.

“What’s different about this,” she said, is that Amazon is challenging not just ALU’s win but also the “legitimacy” of the National Labor Relations Board. The company has claimed the independent federal agency tasked with overseeing union elections exerted “inappropriate and undue influence” with the Staten Island effort. (The NLRB has pushed back at that claim.)

Amazon, which has long said that it prefers working with employees directly versus through a union, has signaled it’s prepared to take its fight through higher courts. In remarks late last year at the New York Times DealBook conference, Amazon CEO Andy Jassy said, in his opinion, the legal battle with the union was “far from over with.” He added: “I think that it’s going to work its way through the NLRB, it’s probably unlikely the NLRB is going to rule against itself, and that has a real chance to end up in federal courts.”

As Bronfenbrenner put it, “Amazon could stall it forever, and they know that.”

The union was likely caught off-guard by the struggles that come after winning an election, Bronfenbrenner said. “They were very focused on the organizing, and not having had a lot of experience, they didn’t really think about the battle for a first contract.”

Now, the public infighting only risks making it harder for ALU to accomplish its goals.

“They have to resolve those differences, and go to the bargaining table as one united organization,” MIT’s Kochan said. “The longer those internal divisions persist and get publicity, the more emboldened Amazon is going to be to say, ‘See, they can’t even agree among themselves, and we don’t have to do anything, but sit on our hands and this thing is going to fail on its own accord.’”

But ultimately, Kochan said he thinks it’s important to remember that the workers are fighting a system that is rigged against them.

“I think the biggest lesson is our labor laws are so badly broken,” he said, “and it needs fundamental change so that we don’t frustrate workers who want to have a union and recognize the uphill battles they have to fight to get a first contract.”

Read the full article here