Financial trouble at the company that supplies more than a fifth of the UK population with water has raised alarm about the dire state of an industry that delivers a resource people can’t live without.

The problems are most acute at Thames Water, London’s utility, but the wider industry across England and Wales is struggling to deliver a reliable service under the weight of huge debts built up since it was sold to private investors over 30 years ago.

The UK water sector is “clearly in a state of multiple crises,” said Dieter Helm, a professor of economic policy at the University of Oxford.

“The day job of maintaining the assets… and achieving required environmental outcomes has not been done very well, and in some cases very badly,” Helm told CNN, adding that “widespread financial engineering” to boost dividend payouts to shareholders had left the industry in a precarious position.

Sewage spills into rivers and coastal waters are routine, leakage is enormous, service is poor, and bills are high — and could go even higher starting in 2025 as mountains of debt make it hard for companies to fix those problems.

Although their track record on leakage and sewage has improved since privatization, according to the water regulator, Ofwat, companies in England and Wales leaked 51 liters of water per person per day between April 2020 and March 2021 — enough to fill more than 1,200 Olympic-size swimming pools every day.

Ofwat said in December that it had “elevated” concerns about the finances of eight of the 17 water utilities it regulates. Together, they provide drinking water and wastewater services to more than 37 million people in England and Wales, or 62% of the population.

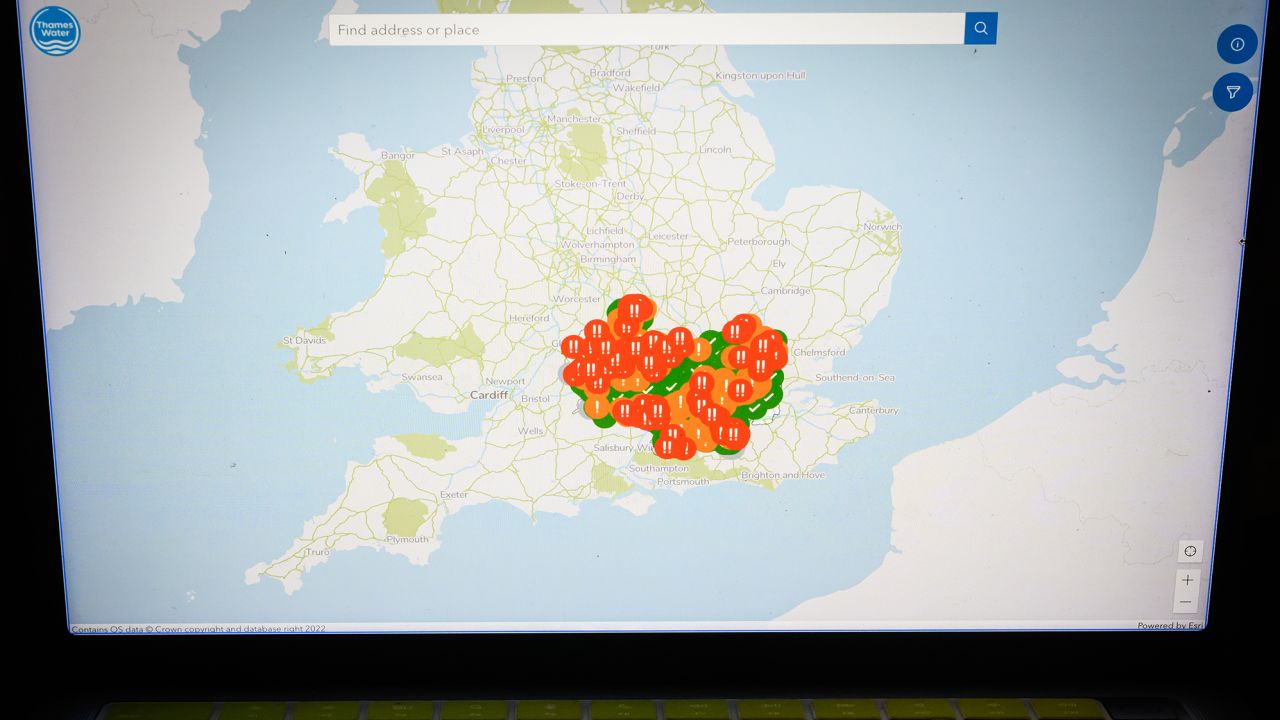

The industry’s long-running problems have been thrust into the spotlight by a looming cash crunch at Thames Water, which serves 15 million people in London and the southeast of England.

Britain’s biggest water company said last week it would need to raise more cash from investors to support its turnaround plan. Days later, the firm was fined £3.3 million ($4.2 million) by a British court after pleading guilty to polluting a river in 2017.

Thames Water has been trying to raise an additional £1 billion ($1.3 billion) from shareholders — including a Canadian pension fund and sovereign wealth funds in China and Abu Dhabi — for more than a year.

But investors, who injected £500 million ($638.6 million) into the firm in March, had “become more concerned about the successful turnaround of the company,” Ofwat’s CEO, David Black, told a committee of lawmakers this week.

Ofwat chairman Iain Coucher suggested the company could need even more cash. “There’s ongoing conversations about the remaining £1 billion, as to whether that is sufficient,” he told the committee.

Thames Water’s need for funds may be most acute — given its £14 billion ($17.5 billion) debt pile and persistently poor performance — but it is not alone in needing to tap investors.

“I understand more companies will announce that they’ve successfully raised equity in the near future,” Black said, noting Yorkshire Water had recently secured £500 million ($638.6 million) from investors.

He added that current investors may not have “appetite” to invest more money into water companies, in which case new investors would have to be found, or the UK government would have to consider temporary public ownership as a last resort.

Water companies in England and Wales were privatized under Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government in 1989, with the rationale that this would unleash the vast investment required to upgrade Britain’s Victorian-era sewage network. But not enough has materialized.

“Money has been taken out, not put in,” said David Hall, a visiting professor at the Public Services International Research Unit at the University of Greenwich in London.

Hall estimates that water companies in England and Wales have collectively paid dividends worth £75 billion ($95.6 billion), when adjusted for inflation, since privatization. Much of those payouts have been funded by huge amounts of new borrowing.

The same companies have racked up more than £60 billion ($76.5 billion) in debt since privatization — when they were debt free — while raising little new money from shareholders, according to Ofwat.

“Virtually every year since privatization there has been no injection of extra capital by shareholders,” Hall told CNN. Instead, investments of some £190 billion ($242 billion) have been funded largely by consumers through higher bills, which have increased by around 40% over this period, taking inflation into account.

The sector is now under growing financial pressure as interest rates soar and more money from customer bills is diverted toward servicing debt — a situation made worse by the prevalence of inflation-linked debt, which causes borrowing costs to climb as prices increase.

Against that backdrop, water companies must invest another £56 billion ($71.4 billion) by 2050 to upgrade infrastructure and tackle sewage spills, which numbered over 300,000 last year.

“When you look at the volume of work that’s required over the next five years and beyond… the quantum of money is huge. We are very concerned about the impact on bills,” Coucher of Ofwat told the committee of lawmakers.

The UK government has held emergency talks over the future of Thames Water, which counts the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System as its biggest shareholder.

S&P Global Ratings placed the company’s debt on negative ratings watch last week, which means it is at risk of a downgrade. S&P said the sudden resignation days earlier of the company’s CEO, Sarah Bentley “increases risks” to the implementation of its transformation plan, “amid uncertainty regarding the timing of additional shareholder injections.”

If Thames Water fails to raise new funds, it may be forced into a special administration regime, which is a form of insolvency that ensures services to customers are maintained while the government tries to find a buyer for the business.

“That’s the backstop option… but we’re still a long way from that position,” Black of Ofwat told BBC radio on Wednesday.

Thames Water, which employs 7,000 people, said last week it had a “strong liquidity position,” including £4.4 billion ($5.6 billion) of cash and committed funding.

Helm, of the University of Oxford, said the ownership structure of the water industry would have to change and that there would be “lots of casualties along the way.”

Hall, of the University of Greenwich, said the government should find a way of bringing the water companies back into public ownership, as it had done with the rail network.

No other country in the world “has sold the entire system to private companies,” he added.

Read the full article here