The Great Recession had a major impact on savers of all types, including institutional investors like pension funds. This quickly stirred debate about the retirement plans offered to public workers, particularly before markets recovered. Despite all of this hubbub, no states completely closed their pension plans. Many states made changes to their pension plans, often significant, with some reducing the value or redesigning benefits, and a few offering a choice between a defined benefit or a defined contribution plan. But states overwhelmingly retained the defined benefit model that promotes career employment.

In 2023, North Dakota chose a different path. The legislature passed and the governor signed a bill that will close the North Dakota Public Employees Retirement System (PERS) main plan for new hires beginning January 1, 2025. This is the latest unfortunate example of a state changing plan design to address a funding problem.

There is no question that the North Dakota legislature was underfunding the pension plan, which was fully funded in 2002. Since 2003, the legislature has made only about 60 percent of the actuarially recommended payment, causing the funded ratio of the plan to fall to 68 percent.

The casual reader likely will think this is a problem. They’re right.

The obvious answer to this problem is to properly and fully fund the plan each year, as so many other states do. Instead, future generations of North Dakota workers will pay the price for this habit of underfunding the PERS plan, even though this “solution” fails to eliminate the existing debt.

For North Dakota, that begs the question: What comes next? And, will the state revisit this decision in the future?

Closing a plan is a long term project, often with damaging unintended consequences. Michigan closed its State Employees Retirement System (SERS) plan as of March 31, 1997. More than 26 years later, there are still thousands of active employees in the closed plan. By the time the final retired member of that plan dies, it will likely have been 70 years or so since the plan was closed.

North Dakota very likely will learn the same lesson other states have learned: closing a pension plan leads to increased costs, while local communities will face challenges recruiting and retaining workers to perform important jobs in their communities.

Not only is closing a plan and fully eliminating its liabilities a lengthy endeavor, it is also a costly one. The actuaries for the closed Michigan SERS plan track the difference in costs stemming from this decision. In 2021, the plan actuary calculated that the decision to close the plan had cost the state over $300 million in additional costs over the past 24 years.

Alaska, while not yet at the same point as Michigan in terms of closing their pension plans, is greatly suffering from the recruitment and retention impacts of no longer offering defined benefit plans to their public employees. Turnover and quits rates are both significantly higher in the defined contribution plans in Alaska than in the now-closed pension plans. Even more concerning: they should expect retention will actually get worse over time, as the remaining pension plan members retire and the state is left with only workers in the DC plans.

The Center for Retirement Research has found that cuts to pensions increased employee turnover in other states, especially for positions in which there are more direct private sector counterparts, e.g., accountants.

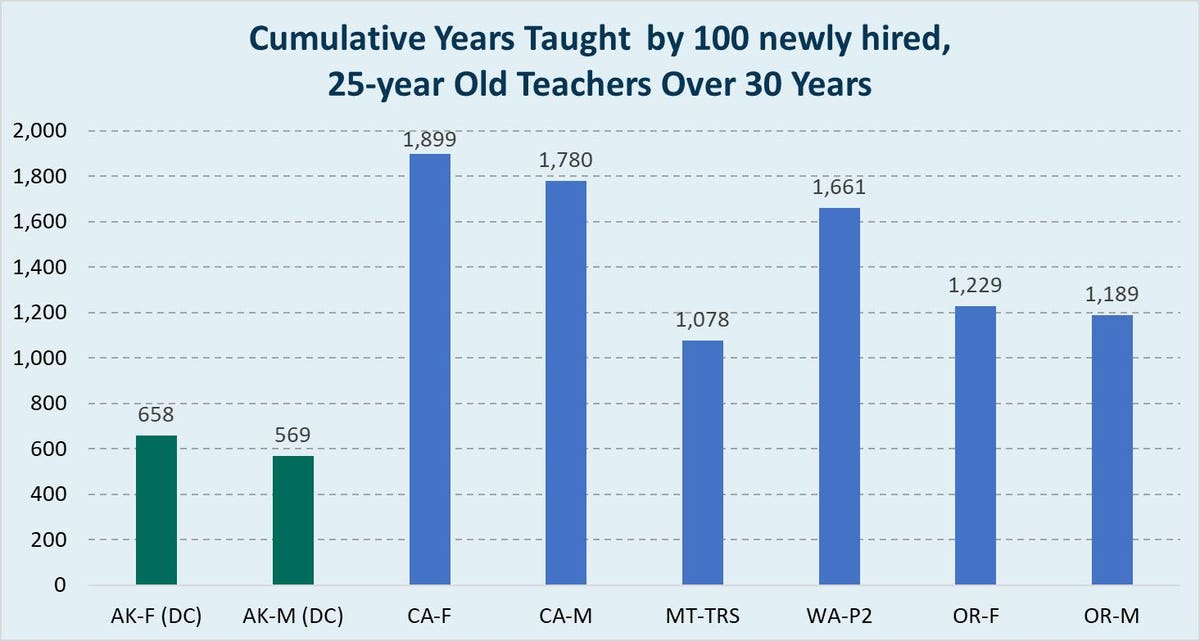

In Alaska, about half of newly hired teachers are leaving before their third year. Early turnover is a common challenge, but not at this level. Based on each plan’s assumptions, Alaska can expect 6.5 years of service on average from a newly hired female teacher. In Washington State and Oregon, it’s 16.6 and 12.3 years of service, respectively.

The challenge of communicating this to policymakers is real, given that no one is tasked with scoring the additional costs of higher turnover and the resulting need for more hiring.

As a result of these struggles, there are serious efforts in Alaska and Michigan to look at either reopening their pension plans completely, or at least reopening for some groups of workers where shortages persist.

A key reason employers offer employee benefits is so employees feel valued. North Dakota is likely destined for the same fate as both Alaska and Michigan, though it may not happen right away. Over time, new workers will understand that their coworkers have a very different deal than they have themselves. The state will find itself paying more for the pension and the new savings plan, only to have employees feel undervalued anyway.

Severe challenges with recruitment and retention, increased costs, and less retirement security for public employees—it’s hard to see who wins from this decision in North Dakota.

Read the full article here