Representatives Nicole Malliotakis (R-NY) and Michelle Steel (R-CA) have introduced the Working Families Tax Cut Act to increase the standard deduction – which would increase the fixed amount of income exempt from taxes. This might not seem like something that would pass as standalone legislation, but it could be attached to a larger bill. At that point, details might change, but the effect would likely be similar.

The bill’s proponents are seeking to offset the costs of inflation for middle-income workers. While that is a laudable goal, new analysis from the Tax Policy Center suggests that the largest tax savings from increasing the standard deduction would go to those with the highest incomes, leaving middle-income workers with just a quarter of the total benefit and low-income families with even less.

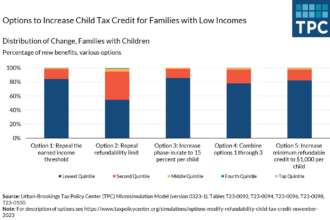

That’s unfortunate, since research suggests that families with low incomes are the most vulnerable to inflation. To better target benefits to low- and middle-income families with children, at reduced cost, Congress could instead modestly expand the child tax credit (CTC) in a variety of ways – that might garner bipartisan support. Even better would be to eliminate the phase-in of the CTC so that low-income families could receive the full benefit, often referred to as full refundability.

The standard deduction reduces tax liability for those who do not claim itemized deductions when filing their taxes. It also ensures that only households with income above certain thresholds will owe any income tax. The proposed legislation would convert the standard deduction to a “guaranteed deduction” with a bonus in 2024 and 2025. The bonus would increase its amount, in those two years, by $4,000 for married couples and $2,000 for single people without children at home, and $3,000 for single people with children at home (head of household filers).

These higher amounts would start to phase out for married couples with adjusted gross income above $400,000 (the corresponding amounts for single and head of household filers are $200,000 and $300,000, respectively). TPC estimates the cost of the proposal at $95.1 billion.

Our progressive tax rate structure means that higher income families benefit more from the standard deduction than lower income families. A family facing the top tax rate of 37 percent saves $1,480 from a $4,000 increase in the standard deduction. A family facing the lowest rate of 10 percent saves just $400. But many low-income families already do not earn enough to owe federal income taxes and would see no benefit from an increase in the standard deduction.

With a tax credit that is fully refundable, on the other hand, all families would receive the same benefit, and families with high incomes would not be favored over families with low- or middle-incomes.

Congress has already balked at making the CTC fully refundable; the current credit phases in so that a household must earn a certain level of income to receive some or all of the CTC. Still, the credit could phase-in more quickly than it does now and still deliver benefits to those most affected by inflation.

About 19 million children in families with low incomes receive less than the full value of the credit because their parents do not earn enough, though the vast majority have some earnings. Phasing the credit in faster would reduce this number.

Last year, TPC, and others, analyzed several plans that would expand the CTC to direct more benefits to children in low-income families. The boldest of the plans TPC analyzed would start phasing in the credit at the first dollar of earnings, phase the credit in faster, and remove the limit on the maximum refundable credit. Together, this would cost about $40 billion over the 10-year budget window, leaving additional room to increase the maximum credit for families with low incomes, as Congress did in 2021.

All of these proposals fall short of the 2021 credit expansion, but could still meaningful for many families with low incomes. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimated making the CTC fully refundable in 2024 would cost just $12 billion. This would help even more low-income families.

An increase in the standard deduction would deliver much less targeted benefits than the CTC plans we analyzed. Sixty percent of benefits go to households in the top 40 percent of the income distribution. The CTC enhancements would deliver over half of benefits to families with children in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution – the families hit hardest by inflation.

Since the expiration of the 2021 expansion of the CTC, families with children have struggled. The evidence demonstrates that the CTC can reduce hardship. Focusing on expanding credits would be more productive than increasing the standard deduction, which will have little impact on those affected most by inflation.

Read the full article here