During the week, Eugene Hall uses his tech savvy to chase down tax cheats, identity thieves and other fiscal frauds. And on football Sundays, he assesses penalties—five and ten yards at a time.

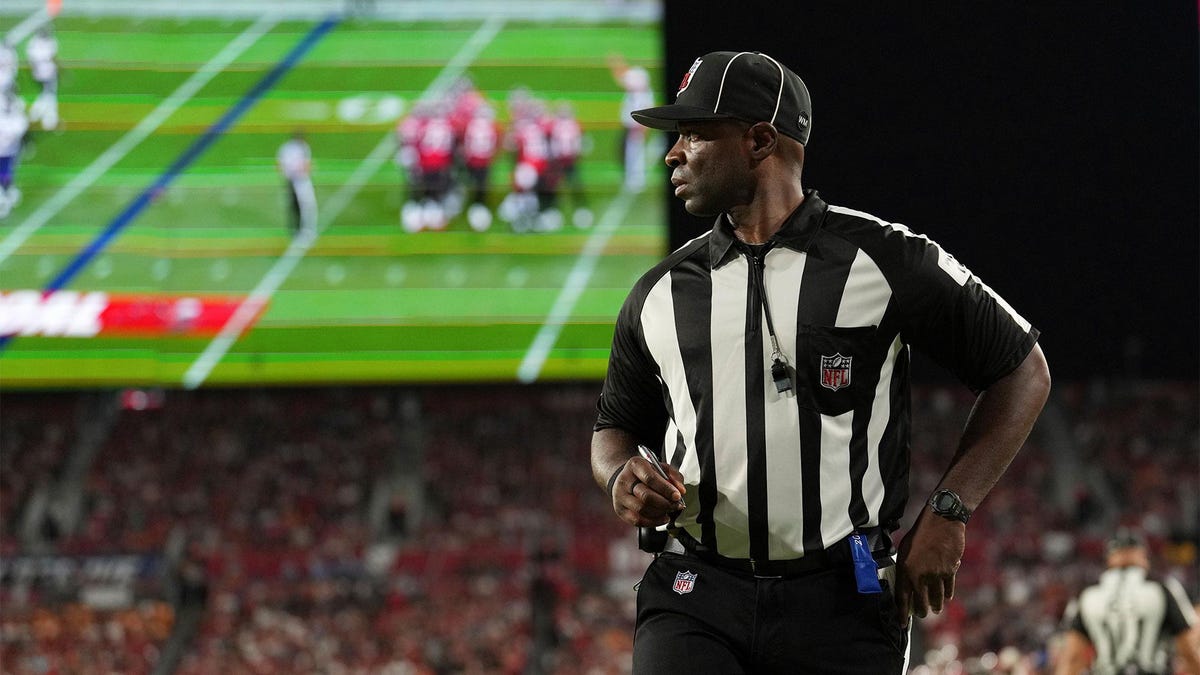

On Sundays, during the NFL season, you can spot Eugene Hall as side judge 103, making critical calls about whether a catch is out of bounds, if there was pass interference, or any other downfield penalties. During the rest of the week, Hall is looking for very different kinds of infractions—as an IRS Criminal Investigation Special Agent tracking down tax cheats and scams that are way out of bounds. Both jobs require an intense focus on detail, analytical abilities, and tact, he says, since sometimes he must deliver bad news to people in a high-stress situation.

“Most of the time when I am talking to coaches on the sideline, it is in a reactionary moment,” says the 45-year-old Hall. “Something on the football field did not go their way and they want answers as to why things happened a certain way.” How he handles that encounter can affect the rest of the game, so he says, “I have to look the coach in the eye and be confident in my answers. However, when I am wrong, then I have to admit my mistakes.”

It’s the same when dealing with business owners at IRS audits or interviewing people in a criminal investigation. Hall found that those moments “tended to be heated situations and I had to be able to speak to people the same as if they were coaches on the sideline.”

Last month, Hall earned his third Super Bowl ring (game day officials get one as well) in only nine NFL seasons, but he also owns up to bigger ambitions—like becoming a supervisor and ultimately a vice-president of officiating at the NFL.

Hall comes by his love of football by birthright, having grown up in Garland, Texas, where high school football famously rules Friday nights. Hall played on the South Garland High School varsity team from his sophomore to senior years as a middle linebacker. But, after his freshman year at the University of North Texas, he stepped back from competitive college play. The next year, he started officiating at intramural games at the university–a gig he kept through graduation.

After college, he started officiating at Pee-Wee and middle school games in the Dallas area, and was offered an opportunity to become an intramural director in the area. Hall thought seriously about taking the job, but his mother cautioned that he would regret it if he didn’t put his B.A. in Finance and Accounting to use. Mom, of course, was right, Hall says.

Hall kept on officiating as a side gig, steadily moving up the local ranks. He called his first high school varsity game in 2004, and by 2006, the year he joined the IRS, was refereeing Division I college games, later moving to the Big 12—one of the Power Five conferences. Hall’s success in elite college football attracted the attention of the NFL, which enrolled him in their developmental program in 2006, officially recruiting him in 2014.

NFL officiating is literally a different ball game. For one thing, it’s more work. Most college teams play 12 regular season games a year. But the NFL has 17 regular season games, plus the pre- and post-season. Hall worked as a side judge for 18 games last season, including the Giants-Eagles divisional playoff and Super Bowl LVII.

Making it to the big game isn’t a matter of luck or seniority. Like Hall’s day job, it’s a numbers game. The NFL rates referees’ performances to help determine who gets to work the Super Bowl, which comes with a bonus pay day—and lots of pressure. An official cannot work a Super Bowl before their 5th season in the league and cannot repeat in consecutive seasons, which means Hall has earned a spot every year he’s been eligible, an achievement that he acknowledges is rare.

After game days, he flies home to Texas and at night, after putting in a full day for the IRS, watches game tape and television replays to analyze plays and calls. That kind of homework, Hall says, makes it easier to spot an infraction, like pass interference, that is out of character for a player.

While the NFL doesn’t release numbers, the top officials reportedly earn more than $200,000 a year. That may sound like good money, but the refs are considered part-time employees and don’t even get health insurance. In fact, most, like Hall, have other jobs—those working Super Bowl LVII included a teacher, a sales rep, and a medical services company CEO.

Hall credits a supportive family (he’s married with four kids, ages 9, 12, 18, and 26), as well as support from the IRS for helping him make it through his busy football season.

Just as in football, Hall has kept moving forward at the IRS. He joined as a Revenue Agent in 2006 and stepped up to auditing in the small business/self-employed division. But during his IRS orientation, another area had piqued his interest—IRS Criminal Investigation. CI, as it’s known, is much smaller than the bureau’s civil side— just 3,700 employees worldwide, about 2,600 of them badge and gun-carrying special agents. The IRS is the only federal agency that can investigate potential criminal violations of the tax code, but CI also works with other law enforcement agencies investigating money laundering, bank secrecy act violations and cybercrime—for example, CI has played a key role in tracking down billions of stolen cryptocurrency and billions of Covid relief fraud.

A few years into his tenure at the IRS, Hall met with CI, which was hunting for prospects with accounting backgrounds and digital forensics skills. After six months of special training at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in 2010, he was sworn in as a special agent and computer investigative specialist who searches for the sort of evidence that field agents need to obtain warrants.

One early win for Hall: helping to stop “Obama schemes” where scammers advertised “free government money” to give away through the “Obama stimulus” program. When folks called in to get their “free” money,” they turned over Social Security numbers and other personally identifiable information. The scammers then used that information to file fake tax returns in the names of those taxpayers—committing identity theft tax fraud.

Among the more recent memorable cases, Hall says, is his work tracking down “ten-percenting” schemes in which a gambler with a winning ticket arranges for another person to cash it, so that a Form W-2G won’t be sent to the IRS reporting the real winner’s taxable winnings. Usually, the person who cashes the ticket charges approximately 10% of the winnings for providing the service.

Hall has his eye on advancing at the IRS, too, with designs on becoming a supervising special agent or special agent in charge. He has a few years to get there—he expects to work for another dozen years or so. (As federal law enforcement officers, IRS special agents usually retire by age 57.) He hopes to be able to help train and develop the next generation of CI agents that the IRS will be hiring soon with extra funding it won last year from Congress.

No, tax work wasn’t a Friday night passion like high school football. But even as a kid, Hall says, he was interested in helping his parents prepare their tax returns and federal tax was his favorite course in college. Say this for Hall: there aren’t many folks who could make not one, but two, successful careers out of a talent for applying mind-bendingly complicated rules.

MORE FROM FORBES

Read the full article here